Perfect Power: How does Paul subvert Greco-Roman notions of power?

Perfect Power: Introduction

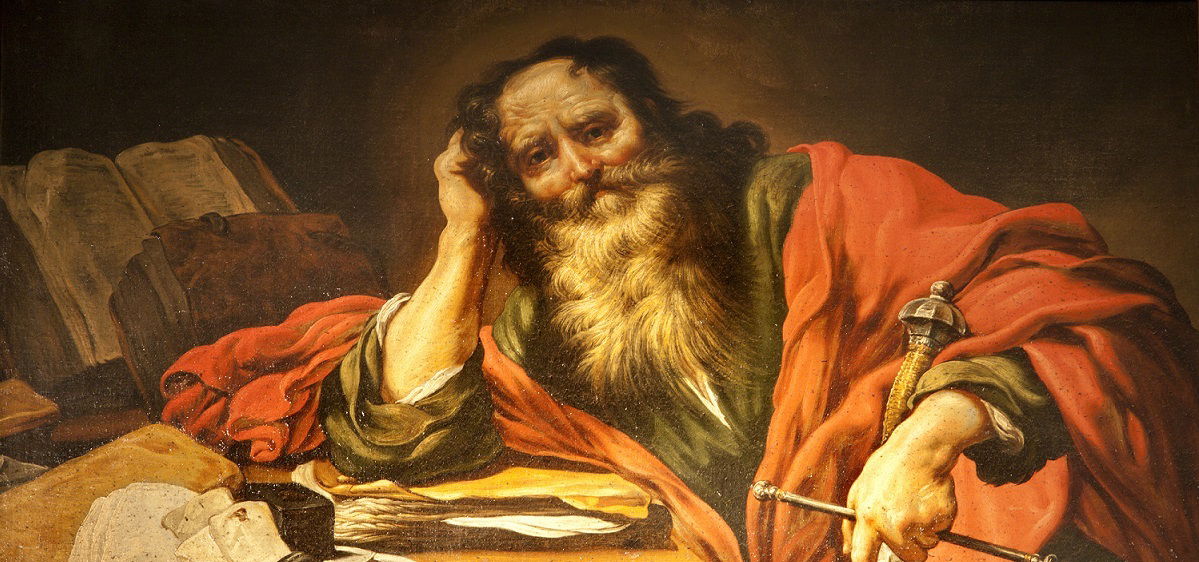

I wonder how many fridge magnets, social media posts or art done by needlework (be it in fabric or on bodies) convey the famous words, ‘when I am weak, then I am strong’,1 or perhaps ‘my grace is sufficient for you’. I wonder how many times we have reminded our own weary souls of such promises when weakness seems a dominant theme. These famous and comforting words, however, are not written in isolation: they exist in context. They are the divinely inspired words of a man attempting to encourage, correct and challenge a church in Corinth in the first century CE.

The infamous Corinthians, with their plethora of contentious cultural practices, which encompass many a Christian faux-pas (from baptising the dead to issues of incest to getting intoxicated at the eucharist)2 are in need of correction, yet again. Whereas those other issues are more apparently wrong, there are other, subtler, cultural issues which Paul needs to confront. Couched in what seems an inspiring speech to endure suffering, Paul is addressing something significant: 1st Century power in Corinth, a Roman Colony, rife with pagan practices and steeped in pagan culture. Paul challenges notions of masculinity and subverts Greco-Roman ideals to bring them in line with Christian ideals.

As Calvin Roetzel argues, ‘Paul deliberately takes on the role of a fool who is also weak and a coward in order to redefine the true nature of manliness.’3 His ‘Fool’s Speech’ is anything but foolish: it is a carefully crafted and intentionally designed message which was needed then, as it is needed now. Power is not found in wealth, status, victory or might: it is radically found in weakness, for when we are weak, then we are strong. This essay seeks to analyse this subversion, paying particular attention to 2 Corinthians 11:22-33.

Paul’s Weaknesses

In the broader context of Second Corinthians, we glean our understanding of the dynamism of this speech: Paul, though largely esteemed in our context, is critiqued in his own. As he builds to his speech, Paul paraphrases specific criticisms laid against him:

- Firstly, Paul is critiqued on the weakness of his presence and contemptible speech: ‘I appeal to you—I, Paul, who am “timid” when face to face with you, but “bold” toward you when away!’; ‘For they say, ‘His letters are weighty and strong, but his bodily presence is weak, and his speech contemptible.’’’4

- Secondly, he is critiqued for not accepting their finances: ‘Let it be assumed that I did not burden you. Nevertheless (you say) since I was crafty, I took you in by deceit.’5

These critiques are not haphazard, but rather more specific insults aimed at his masculinity, which have been propagated to convince ‘Corinthian Christians of Paul’s inadequacy as an apostle.’6 As Jennifer Larson summarises, ‘The accusations of physical weakness, lamentable public speaking skills and a refusal to accept financial support are not separate charges but interconnected attacks against Paul that, taken together, challenge Paul’s manliness.’7 When we compare these accusations with Greco-Roman ideals of both masculinity and power, it becomes apparent that Paul is not simply being criticised as a less favoured ‘preacher’, but that Paul is viewed as weak, effeminate and lacking in masculine power.

Masculinity, in this context, was only partially attributed to anatomy; it was in large part ‘identified with social and political dominance.’ 8 Male slaves, for example, had impaired masculinity as they lacked autonomy, whereas noble birth was immutable; ‘masculinity was a matter of perception.’9

Elite men were consequently concerned with the maintenance of their masculinity and the projection of their power: their positions of power must be displayed and justified. This was achieved through a variety of devices, from their personal dignity and bodily integrity to details of appearance. One such essential device was oratory. Whereas for us, oratorial skill might be a desirable skill, in this Greco-Roman culture, it was closely tied with masculinity as an important marker of social status and thus of social dominance.10 Libanius, a Greek teacher of rhetoric, for example, admonished his pupils to ‘Use your tongues to make yourselves superior to your slaves’.11

It was a measure of one’s masculine superiority, and thus for Paul to be untrained, weak and unskilled was a ‘severe denigration of his manliness’.12 As we read of his ‘strong letters’, the aim is not to compliment Paul’s impressive letter writing, but rather to criticise his weak physical presence and his poor public speaking, implying that these defects are not appropriate traits of apostleship.13 Furthermore, Paul displays masculine weakness in his refusal to accept financial support. What may be viewed as a virtue in our culture is a display of weakness in theirs, calling into question his power once again. The crux of the matter is that Paul prefers to engage in physical labour to earn his finances rather than accept financial support. Culturally, however, for a teacher to do so was perceived as degrading.14 According to Cicero, physical work was considered pathetic and vulgar, for he thought that receiving a wage was a form of slavery.15 Their perception of power involved having subordinates do this type of work rather than restricting one’s own autonomy by being made subordinate to others. The notion that Paul would submit himself to this kind of degradation as a teacher severely undermined his authority over the Church in Corinth.

To us, these critiques are fairly inoffensive; they are, however, dangerous criticisms. His opponents call into question his masculinity and consequently undermine his apostleship and authority over them.16 Brent Shaw goes as far as to write that this association with weakness, in manual work, weak speech and unimpressive appearance, equate with being morally inferior: to be weak was to be ‘poor, submissive, slavish, womanish, and therefore [have] an indelible connection with shame, humiliation, degradation and inexorably, with that which was morally bad.’17 This evaluation, then, is particularly damaging to a man who is meant to be a moral leader and example to the early Church, who dares to say ‘imitate me, as I imitate Christ.’18 If he is morally inferior, weak and effeminate, what does that therefore say of his Jesus?

Jewish Strength

The preceding chapters in Second Corinthians already ‘locate Paul between Graeco-Roman paganism on the one side and traditional Judaism on the other.’19 There is consequent debate about the degree to which Paul is conforming to cultural ideals of power, and if so, to whose: Jew or Gentile? To prove ‘his manliness’ and increase ‘his authority’, some argue that he ‘uses standards of hegemonic masculinity in the Greco-Roman world’, ‘paying particular reference to himself as paterfamilias and warrior.’

On the other hand, Paul also ‘employs ethnic standards of masculinity of the Hellenistic Jewish world that associate manliness with endurances of foreign oppression.’20 For Kim, he is ‘simply referencing different standards depending on the context and the assumed reader.’21 I would argue, however, than rather than utilising whatever image is available to project strength to whoever is listening, Paul is doing something more strategic: he aligns with traditional Jewish beliefs, (considering Jesus as the Jewish Messiah and therefore a continuation of their Torah and tradition) whilst also ‘distanc[ing] himself from Greco-Roman ideology’, as Hezser argues,22 or more specifically, subverting it.

Paul intentionally begins with an appeal to Jewish values.23 In his opening three questions, Paul links himself ‘to the Hebrew Bible, the land of Israel, and Jesus himself.’24 These connections mark his allegiance ‘to the ethnic group from which the Torah and Jesus originated.’25 He is consequently allying himself with Jewish values. Hezser infers that this implies that ‘his competitors stressed their Jewish origin’ and thus Paul is maintaining that ‘he is equal to them in this regard.’26 This cannot be verified; however, what seems more important is that Paul is validating this measure of strength, regardless of who his primary opponents are. Paul positions himself as a servant, or slave, of Christ. To the Roman, this is a sign of weakness; to the Jew, suffering is ‘a masculine trait that increases his authority and cements his apostleship.’27

Paul consequently introduces himself as a servant of Christ in a way congruent with the Old Testament values. As Hezser unpacks, the ‘term ‘servant of Christ’ is already reminiscent of the servant or ‘slave’ of God in Deutero-Isaiah (Isa 40-55), who is destined to reveal the truth amongst the nations (Isa 42:1b) and to redeem others through his own sufferings (Isa 52:13-15).’ In Deutero-Isaiah, Israel itself identifies with God’s suffering servant, and this service to God entails ‘various kinds of tribulations and humiliations (53:3-9)’. It is in this suffering that redemption is found.28 Paul is therefore situating himself in a tradition whereby God not only tolerates, or even turns around suffering, but requires it. For the Hellenistic Jew in Corinth, this is not a subversion of notions of power, but a reinforcement of their own long-held values. Paul has introduced himself ‘as a better ‘servant of Christ’ than his competitors’29 and consequently a fit leader and justified apostle precisely because of his suffering and weakness.

Gentile Weakness

Kim argues that ‘Paul proves his manliness’ to ‘Jewish Christians with the standards of Hellenistic Jewish masculinity’, however, she continues that he also proves it to ‘Gentile Christians with the standards of hegemonic masculinity in Roman society.’30 I would disagree. Though he is appealing to Hellenistic Jewish masculinity, I do not think he employs the same tactic with Roman values. Rather than attempting to comply with their ideals of strength, he appropriates their images and does a more creative work, parodying and subverting their understanding of power. Whereas when he lists his litany of suffering, there is a congruence with Jewish standards of strength, it is incongruent with Roman standards. Paul ‘boasts’ in a long and impressively awful list of his suffering (‘I have worked much harder, been in prison more frequently, been flogged more severely, and been exposed to death again and again…’31), and some commentators interpret this section flatly, taking it as a reluctant but genuine boast of his ‘apostolic trials’;32 this argument, however, overlooks the deeper transformative work that Paul is attempting. Though he is aligning himself with the redemptive quality of suffering in the Jewish understanding, he is not simply listing his virtues-via-violence to brag about his manliness. To read it as such is to discount the Greco-Roman audience and either assume a Jewish only audience or to impose upon the text a modern understanding of virtue through suffering.

As N. T. Wright illustrates, if this were an ancient curriculum vitae, it would immediately disqualify Paul from his status as masculine man, leader and power-wielder.33 Instead, in listing his suffering, he parades before them the most embarrassing and shameful events of his life – at least (and this seems to be the point), to a Roman. As Wright continues, ‘in the ancient world all these [instances of suffering] would mean not only that you are an unsavoury character whom most people rightly avoided, but that the gods must be angry with you as well.’34 To endure prisons, beatings, official floggings, stoning (and all despite the protection afforded to Paul as a Roman Citizen) is staggering. This goes beyond misfortune or happenstance and positions Paul as a dangerous figure. Furthermore, to suffer hardship by means of hunger, nakedness, exposure, and sleep deprivation is extremely demeaning. Though Paul was ‘certainly not alone in presenting ancient travel in such a bad light,’35 this goes beyond a trip gone awry: Paul lacked the necessities that even a slave would be afforded. Furthermore, ‘cultured and educated people would have insisted on a military escort, or at least on travelling with people who could protect them.’36

Paul does not position himself as a leader to be trusted, admired or followed: he is a man to be avoided. As he concludes the list of physical sufferings, Paul admits to feeling the ‘pressure’ of the churches; the Greek word used (ἐπίστασις, episustasis) alludes to uprising, disturbance or insurrection.37 Once again, Paul is positioned as a failure. He admits to rebellion amongst not only the Corinthians, but more broadly in other churches. This clause, coupled with his admission of temptation, implies that Paul is indeed aligning himself with the Roman assumption that Shaw suggests: that to lack in masculinity means to have ‘an indelible connection with shame, humiliation, degradation’ and more damningly, to have a connection with ‘that which was morally bad.’38 Though Paul is not confessing to sin, but rather to temptation, he nevertheless risks being perceived as physically, mentally and spiritually weak.

This shame, humiliation and degradation are epitomised in the climax of his list.39 In referencing his escape from Damascus, Paul reaches the apex of his boasting: he was lowered in a basket down a wall. To modern readers, this feels anti-climactic – we would prefer to suffer this somewhat humiliating retreat over being stoned or flogged. Paul is, however, once again doing more than meets the eye: he is parodying a Roman military victory. As he recounts his ignoble retreat from Damascus, he appropriates the Corona Muralis. The ‘Crown of the Wall’ was a highly prized award given to the first soldier to scale the enemy's wall. In a culture which prized military might above all, to receive this literal crown at Rome was an honour held in great esteem, comparable perhaps to our Victoria Cross.

The Roman mode of war demanded laying siege to cities and taking extraordinary risks to ensure victory; this encompassed scaling walls and facing attack in a variety of lethal ways, from ladders being pushed to boiling liquids being poured, to hand-to-hand combat should you ever survive that long.40 The Corona Muralis was therefore a great incentivisation to soldiers: ‘Manliness’, after all, ‘was not a birthright. It was something that had to be won’.41;42;43 In the chaos and confusion of war, many a man could have claimed this honour, and so to ensure that only the true victor claimed the crown, the soldier was required to go to Rome and swear by the gods that he truly was the first. This is the most convincing explanation as to why Paul concludes his list by invoking the name of ‘The God and Father of the Lord Jesus, who is to be praised forever,’ who knows that he is ‘not lying.’44 In a parody of this Roman custom, Paul invokes the name of his God, whom he swears by, not that he was the first up the wall, but the first down the wall: ‘Rather than the conquering hero, Paul [is] the battlefield coward.’45 The Corinthians are therefore confronted with this radically opposing view of power. This seems to be the embodiment of what Paul is doing: he is presenting a new way of life, a new power, a new masculinity – of one who even escapes down the wall, ‘humiliated and defeated in the eyes of the world’, eluding the powers of the world by God's grace, not military prowess.46

Larson, however, argues that despite this clear subversion, Paul ‘conform[s] to the Corinthians’ expectation about the qualities of a leader’ because Paul emphasizes his masculinity by using the image of paterfamilias (11.2-3; 12.14) and warrior (10.3-5).47 Is he, therefore, less radical than we think, and even reinforcing warfare and patriarchal ideals? I would go further, however, and argue that this is not conformity, but rather a continuation of the same theme of subversion. Paul is using the image of a warrior, but as a springboard to subversion; he writes that ‘we do not wage war according to human standards…’48 He appropriates the image of a warrior, but we battle strongholds, destroy arguments, take captive thoughts. Likewise, as he appropriates paterfamilias he assumes the role of a father, giving away his daughter in marriage, but it is an image altered.49 Kim argues that a paterfamilias ‘has absolute power and authority’;50 this is therefore conformity. I, however, interpret this differently in light of Paul’s apparent strategy. As there was an assumed level of anxiety to fatherhood around his daughters – their chasteness, their safety, their successful partnership – Paul uses this accepted framework to speak of his concern not as an actual father, but as a spiritual father to the Church.51 He utilises a familiar image in order to do something new: the men in the church, with their projected and protected masculinity, must now see themselves as chaste brides: hardly the picture of male power.

As Peterson writes, ‘Though Paul uses images of social power to present himself as one with authority to the Corinthians, these images – which are potentially abusive and manipulative – are transformed by the cross.’52 This is not conformity but confrontation. As Peterson argues, ‘Paul's ‘fool's boast’ is a watershed in this argumentation’ because Paul has made it clear: ‘in Paul's weakness dwells the power of Christ (12:9-10).’ 53 It is not found in military might as they understand it; it is not found in being first up the wall; it is not found in being the successful head of a household, or indeed in any other male accomplishments or markers of hegemonic masculinity, but rather in ‘weakness and failure’, where ‘God's power for salvation is at work.’54 What the Jew might already comprehend from Torah, the Gentile must also learn: God’s ‘grace is sufficient’: ‘power is made perfect in weakness’.55 By God's grace, Paul's weakness has been transformed into the vehicle of God's power. Pagan images have been utilised, laden with their powerful implications, but ‘the images do not remain unaltered’: they are transformed ‘in the light of the cross.’56

The Weak Victor

Paul’s subversion of power is essential to Corinth’s discipleship. They needed to comprehend the weight of communion, to abstain from incestuous practices, and learn to live morally appropriate lives; however, understanding the nature of power is arguably more important. This confrontation, which many modern readers could miss, is essential not only to how they conducted themselves in the church, but as a baseline condition of being the Church. Comprehending this kind of weak-strength was imperative to their understanding of salvation. Paul is undoubtedly aware that, particularly to ‘elite Roman males, a ‘muscular Jesus’ would have appealed far more than a Jesus whose triumph was revealed in his weakness.’57 If Paul ‘fails’ as a man and a leader in their estimation, Jesus would also inevitably fall short. Going beyond even the whole litany of humiliations and degradations that Paul suffered, to be crucified was worse.

This punishment, which we are so familiar with as an icon of hope, was an instrument of the cruellest death. A fate not permitted to Roman citizens, crucifixion was designed to be physical agony and humiliation and degradation of the severest form. As historian Tom Holland expounds, ‘Crucifixion, in the opinion of Roman intellectuals, was not a punishment just like any other. It was one peculiarly suited to slaves. To be hung naked, helpless to beat away the clamorous birds, 'long in agony', as the philosopher Seneca put it, 'swelling with ugly weals on shoulder and chest', was the very worst of fates’.58 It rendered its victim helpless, hopeless and humiliated. Paul recognises that if elite Roman males are to accept a crucified Saviour, they would need to reframe their definition of strength and weakness. Familiarity with Christ’s cross has desensitised us to what Paul recognised: it was a scandal.

This was no ‘muscular Jesus’, but a man who died on a weapon befitting slaves: those whose masculinity was severely impeded. And yet, this ‘ancient tool of imperial power’ has become ‘a symbol of a transfiguration in the affairs of humanity as profound and far-reaching as any in history’.59 At the heart of Christianity, it is because 'God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong.'60 As Holland surmises, ‘It is the audacity of it – the audacity of finding in a twisted and defeated corpse the glory of the creator of the universe – that serves to explain, more surely than anything else, the sheer strangeness of Christianity, and of the civilisation to which it gave birth.’61 Paul recognises: this is a scandal62 – and if Jews and Gentiles alike cannot recognise and accept the wonder in weakness, then hope is lost. As he draws his letter to a close, Paul makes explicit what he has been working towards: ‘For [Jesus] was crucified in weakness, but lives by the power of God. For we are weak in him, but in dealing with you we will live with him by the power of God.’63

Jesus is the weak victor, the suffering leader, the emasculated epitome of masculinity. What looks like weakness is indeed a great display of strength. Consequently, Paul, who is ‘weak’ in his dealings with them, lives by a divine power far exceeding Roman ideals. Paul’s own suffering is used as an example, connecting him to the crucified King ‘as an imitatio Christi.’64 Even the infamous ‘thorn in his flesh’ came from God,65 and perhaps the metaphor of a thorn is selected purposefully. It is in this thorny-weakness that God reveals, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness.’66 This is why he boasts ‘all the more gladly’ of his weaknesses, ‘so that the power of Christ may dwell in me…’67 His weaknesses, not his strengths, connect him to Christ’s power. He is found in ‘full submission’ to this scandalous Jesus, where he discovers the ‘source of his strength and manliness.’68

Paul therefore redefines the nature of power: ‘emblems of powerlessness and unmanliness become tokens of divine power and masculinity.’69 Perilously, if the Corinthian church cannot grasp the strength in the cross, it cannot be the church at all. If, however, Paul redefines their ideals of perfect power, not only will they be liberated in their own lives to allow for weaknesses, as well as from male anxiety in maintaining their masculinity, but they will also grasp the foundational truth of the gospel: that God himself died in weakness, so that we who are weak might be made strong. In our weakness, we too are imitatio Christi.

Perfect Power: Conclusion

In this Greco-Roman world, where physical beauty and strength were essential elements of masculinity, where speech and stature were hallmarks of strength, where subordinates were lesser and your command over others superior, Paul came up short, and in his deficiencies, his manliness is ‘undermined’.70 Paul therefore mounts a defence, not by merely touting his masculine accomplishments but rather in redefining (and reaffirming) what masculine power looks like.

Firstly, as Hezser summarises, ‘instead of Israel being the slave of God, Paul presents himself as servant of Christ’, thus individualising and Christianising the ‘prophetic prototype’.71 He situates himself in an accepted Jewish tradition and carries it through to Christianity. Secondly, he recognises that the critiques leveraged against him are Roman ones, and rather than conforming to win over his opponents, Paul subverts Pagan values which stand opposed to Christian ideals: ‘Paul engaged cultural expectations about manliness and its relation to authority’ with the aim of reforming them.72 Paul understands that if the church in Corinth is to endure and retain its position as the church, they must grasp what perfect power is: it is not found in Roman ideals, and neither is it fully revealed in Jewish ones: it is found in the Jewish Messiah, the fulfilment of Old Testament promises, who gave his life as suffering servant – Christianity is, after all, ‘a revolution that has, at its molten heart, the image of a god dead upon an implement of torture.’73

Whereas the Roman world admired the corona muralis, Christians must live in wonder and worship of a crown of thorns and appreciate that we will one day cast our ‘crowns’ before him.74 Christianity reveals ‘a momentous truth: that to be a victim might be a source of strength.’75 Therefore, for the Corinthians, so too for us: we can stop the performance, let go of the anxiety, and boldly proclaim: I am weak! And in Jesus, I am therefore strong.

Bibliography

Cicero, Off. 1.150. Garland, D. E., 1989, Paul’s Apostolic Authority: The Power of Christ Sustaining Weakness (2 Corinthians 10–13), (RevExp 86: 371-89).

Gleason, M. W., 1995, Making Men: Sophists and Self-Presentation in Ancient Rome (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Holland, T., 2019/04/20, The way of the cross: Christianity's undying influence, (The Spectator).

Kim, K. M. (2021). Paul’s Defense: Masculinity and Authority in 2 Corinthians 10–13. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 44(1).

Kruse, C. G., 2008, TNTC: 2 Corinthians, (Illinois: Intervarsity Press).

Larson, J., 2004, Paul’s Masculinity, (Journal of Biblical Literature, 123(1)). Libanius, Or. 35.15. Livy, History, 26.48.5.

Mayordomo M., 2011, ‘ACT LIKE MEN!’ (1 Cor 16:13): Paul’s Exhortation in Different Historical Contexts, (CrossCurrents 61: 515-28).

Peterson, B. K. 1998, ‘Conquest, control, and the cross: Paul's self-portrayal in 2 Corinthians 10-13’, Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology; Richmond, Vol. 52, Issue 3.

Polybius, Histories, 6.39.5.

Reimund Bieringer, Emmanuel Nathan, Didier Pollefeyt, and Peter J Tomson, 2014, Second Corinthians in the Perspective of Late Second Temple Judaism, (Boston: Brill.)

Hezser, Catherine, The ‘Fool’s Speech’ in the Context of Ancient Jewish and Greaco-Roman Culture.

Roetzel, C. J., 2009, The Language of War (2 Cor. 10:1-6) and the Language of Weakness (2 Cor. 11:21b–13:10), (BibInt 17).

Shaw, B. D., 1996, Body/Power/Identity: Passions of the Martyrs, (JECS 4: 269-312).

Sumney, J. L. 1990, Identifying Paul’s Opponents: The Question of Method in 2 Corinthians (Sheffield: JSOT Press).

Wilson Brittany E., 2015, Unmanly Men: Refigurations of Masculinity in Luke–Acts (New York: Oxford University Press).

Wright, N. T., 2012, Paul for Everyone: 2 Corinthians, (London: SPCK).